The South Bay holds a rich history, relatively unknown to many who reside here. It is a beautiful and tragic story that spans thousands of years. The South Bay, as it stands today, is relatively new, but that’s only because we recently declared it to be so. The truth is, we are living on the very ground once known as Tovaangar, the bountiful home of the Tongva people. Once a land that spanned from Palos Verdes to San Bernardino, from Saddleback Mountain to the San Fernando Valley.

Who are the Gabrielino/Tongva Nation?

According to the Lost Cultures: Living Legacies podcast, the Gabrielino/Tongva are the aboriginal tribe of the Los Angeles Basin and four Southern Channel Islands, the true First Angelenos. Believed to be descendants of native people who migrated from Nevada anywhere between three thousand and ten thousand years ago, their lands used to encompass 1.5 million acres. Often regarded as the first “beach people,” they had a deep expertise with the ocean and coast. Their villages were thriving economic centers, rooted in strong family ties and a harmonious relationship with Mother Earth. Trade with other tribes, and even with people as far as Russia, helped the Tongva establish tight-knit communities and build a reputation for producing valuable, well-crafted goods. Each village in Tovaangar had its own government—there was no singular chief, and leadership roles were passed down hereditarily. Occasionally, multiple villages would gather for important ceremonial purposes, but this was not commonplace.

Most of all, the Tongva are our neighbors, friends, and coworkers—past, present, and future. The protectors of the land we live on, the land we harvest, pollute, and regenerate. They are native, and they never left. In fact, it was us who moved in.

Where did they live?

The South Bay region of the Los Angeles Basin was home to several Tongva villages, including Ongovonga, Chaawvenga, Kiingkenga, Swaanga, Soabit, and Amupubit, covering land from Redondo Beach to Carson. These villages were relatively small, with some accommodating around 100 people, likely due to inland migration during seasons where living conditions were unsuitable. The Palos Verdes Peninsula was a particularly important settlement area for coastal Tongva communities, known for its role in trade and abundant resources. Due to its proximity to Pimu (Catalina Island), it became a hub for congregation and cultural exchange. In fact, Juan Manuel Cabrillo referred to San Pedro as “the Bay of Smokes” in 1542, likely because of smoke signals used for communication between the island and the mainland.

Some major native sites in the South Bay, like Malaga Cove and Abalone Cove, are familiar landmarks today, but they hold significant archaeological evidence of ancient Tongva communities. Artifacts such as animal and fish bones, shells, burials, cremations, and cairns reflect the Tongva’s way of life, diet, and cultural traditions.

The Impact of the California Missions

Unfortunately, the lively and thriving Tongva community was harshly disrupted upon the arrival of Spanish settlers and the establishment of Catholic missions. Between 1769 and 1833, 21 missions were founded across California, leading to the forced relocation of nearly all Indigenous tribes in the region. Most of the South Bay Tongva were moved to Mission San Gabriel, with smaller numbers sent to Mission San Juan Capistrano or Mission San Fernando.

The Spanish arrival brought cultural devastation, manifesting through invasive species, disease, forced assimilation, and slavery. What was presented as salvation resulted in belittlement, disrespect, and abuse. Many Tongva were compelled to abandon their heritage and language or practice their traditions in secret, risking their livelihoods and lives in the process. It is thought that prior to the California missions, there were about 300,000 Native Californians. By 1834, scholars believe there were only about 20,000 remaining.

Even after the Mexican government enacted the Mexican Secularization Act in 1833 and seized the missions, freeing the Indigenous people held there, the redistribution of land failed to benefit the Tongva and other tribes. Instead, much of the land was granted to private owners, leaving the Tongva as a people without land on territory that was once entirely their own. This displacement marked the beginning of a long struggle for the Tongva to reclaim even a fraction of what was rightfully theirs.

So, what came next?

After the missions came over a hundred years of exclusive and oppressive laws working against the remaining native populations. The 1850 Act for the Government and Protection of Indians enabled the indentured servitude of natives through forceful and deceitful means throughout California. Being sold into indentured servitude at auction was a punishment for vagrancy, which could mean anything from loitering to being unemployed. Once sold, the individual would be required to provide free labor for four months to their “owner.” Natives were inherently put at risk simply for existing. On top of that, the Gold Rush brought the systematic elimination of native peoples due to their presence being viewed as an “inconvenience” to the white settlers. It came to the point that bounties were put on their heads, giving more incentive for their slaughter. Their treatment by colonists was nothing short of abhorrent and heartless, and the government, for the most part supported it. In 1891, the California government passed The Mission Indian Relief Act, seemingly to protect the rights of natives and re-distribute lands under a special Indian agency. This resulted in the addition of about 12,000 acres to the original 640-acre reservation in the Coachella Valley, California and made the Pala reservation permanent.

What happened in LA?

In Los Angeles, the Tongva faced not only the laws of California, but also their own onslaught of legal/cultural actions, some providing efforts to redefine the image of indigenous Angelinos. In 1852, the Los Angeles Star published Hugo Reid’s letters about The Indians of Los Angeles County. Reid was married to a Gabrieleno woman, and his letters detailed the lives and cultures of natives at San Gabriel and San Fernando Missions. These were especially unique at the time because they provided a new perspective, and discussed the serious and harmful impacts of the mission system’s forced labor and cultural destruction. In 1890, there was an exodus of Tongva natives to the St. Boniface Indian Industrial School, where cultural destruction continued due to the teacher’s belief that the students were incapable of learning complex topics, and should rather be taught to work blue collar jobs and focus on salvation and assimilation. In 1903, another addition of ethnographic and linguistic knowledge about the Tongva people was delivered to Biological Survey naturalist C. Hart Merriam, ultimately expanding the understanding of the tribe’s culture on a larger scale.

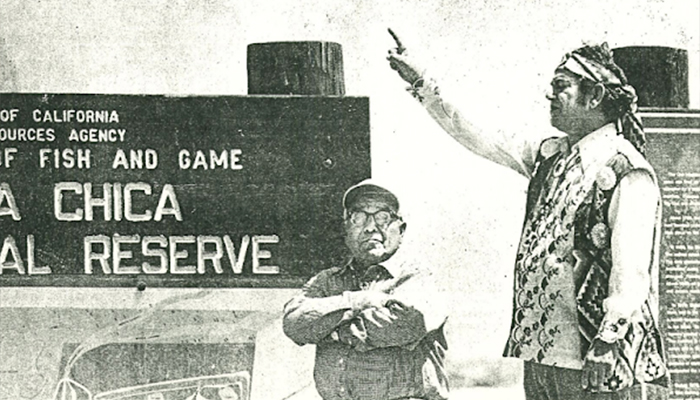

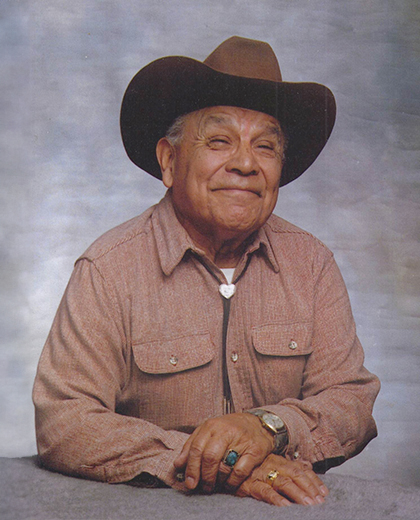

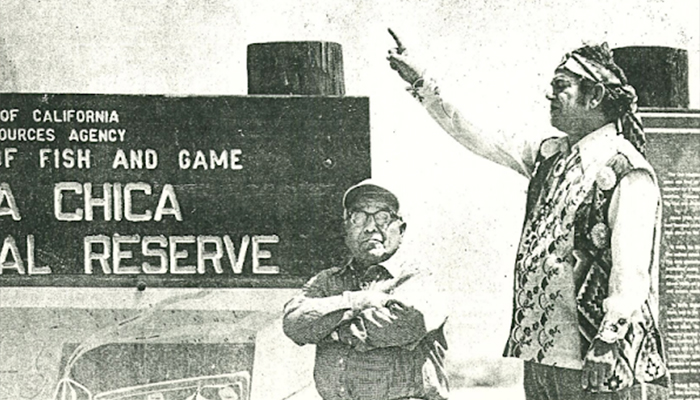

In the 1900s, Important gains for Gabrielino/Tongva visibility had begun. In 1928, the first of many official enrollments of Gabrieleno/Tongva people was added into the California Indian Census. In 1951, the Tongva retained legal counsel per The Bureau of Indian Affairs. In 1972, Gabrielino/Tongva people received settlement funds from the judgment of the Indian Claims Commission. In 1984, the tribe transitioned from traditional leadership to formal tribal organization when James (“Jim”) Velasquez was instated as chieftain. In 1994 The State of California officially recognized the Gabrielino/Tongva tribe, naming them the aboriginal tribe of the Los Angeles Basin with an emphasis on the continued existence of the native community. In 2013, The Los Angeles City Council, in Resolution 13-1285, declared its support of the Gabrielino/Tongva Nation in its efforts to restore a government-to-government relationship with the United States.

Los Angeles County is making strides in strengthening the relationship between the Gabrielino/Tongva Nation and the government as the native population works to rebuild their connection with the culture that was taken from them. Although there are still significant changes needed to repair the damage inflicted upon California’s native people, we are on the cusp of transformation.

Lasting Impact and Moves Towards Changeair

According to Mapping Indigenous LA, Los Angeles has the largest Indigenous population in the U.S. This includes not only the Gabrielino/Tongva people native to the region but also Indigenous diasporas from the Pacific Islands and Latin America. While aspects of these cultures are still celebrated, it’s crucial to recognize the oppressive colonial history that stifled their autonomy and growth. From the first Spanish explorers on Catalina Island in 1542, to the missions, bounty-hunting during the Gold Rush, and boarding schools, generations of violent cultural suppression and forced assimilation aimed to erase those who originally inhabited this land.

Despite a lack of federal recognition, the Tongva people have shown remarkable resilience. They have established their own Constitution and governing body to protect and conserve their culture, lands, and history as a unified Gabrielino/Tongva Nation, with a membership of more than 700 tribal citizens descended from a bona fide Gabrielino/Tongva ancestor. Their efforts are particularly vital because, unlike many other Southern California tribes, the Tongva have never had any land returned to them, in part due to the high value of LA County real estate. Although the Federal Indian Claims Commission found that the Tongva were wrongfully deprived of 1,553,772 acres of land, they only seek to reclaim less than .005% of that land once they are federally recognized.

Most importantly, the Tongva are still here, and their fight for their homeland continues. Both the small efforts, like learning about their history and culture, and the larger initiatives, such as reconstructing the Tongva language, play vital roles in moving them closer to success. These actions contribute to the appreciation, visibility, and recognition the Tongva people rightfully deserve, as they work toward reclaiming their heritage and rightful place on their ancestral lands.

Where can I find more information and resources about the Tongva people?

There are plenty of sources to learn more about not only the descendants of this tribe, but the history of the land and our natural resources that helped define their culture.

Native Narratives: Tongva Traditions

The Tongva: A Lasting Influence on Los Angeles

Great Migration

Native Narratives: Perspectives on the Anza Trail

Mapping the Tongva Villages of L.A.’s Past

Gabrielino/Tongva Nation

O, My Ancestor: Recognition and Renewal for the Gabrielino-Tongva People of the Los Angeles Area

Tongva Tribe Timeline

Sources Used:

https://www.history.com/topics/religion/california-missions

https://hacla.org/sites/default/files/Development%20Services/Documents/4.14%20Tribal

https://collections.theautry.org/mwebmedia/media_001/5SitePre_Fin.htm

https://gabrielinotongva.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/GTN-Constitution-February-22-2020.pdf

https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=a9e370db955a45ba99c52fb31f31f1fc#

https://mila.ss.ucla.edu/

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/goldrush-act-for-government-and-protection-of-indians/#:~:text=Laws%20against%20Native%20Americans,of%20Indian%20crimes%20with%20punishments.

https://www.loc.gov/item/68008964/

https://dorothyramonlearningcenter.substack.com/p/the-boots-of-st-boniface

Pictures Reference:

https://gabrielinotongva.org/history/